Maybe Schizophrenia Won’t Disappear Anytime Soon

Part I. How Schizophrenia Is Treated Now

The thing is, the approach to treating schizophrenia has not changed much in the past 75 years.

The Start of a Revolution in Treating Schizophrenia

A Bit of Pharmacology History

In 1950, a big breakthrough changed how schizophrenia was treated. Chlorpromazine (Thorazine), a medicine that helped ease symptoms of psychosis, was discovered by accident. Before this, treatments were often harsh and ineffective, like insulin coma, lobotomy, heavy sedation, or early, crude forms of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). (Modern ECT is much gentler and safer and even suitable for pregnant women and the elderly.)

Chlorpromazine paved the way for a flood of new medications: haloperidol (Haldol) in 1958, then others like trifluoperazine (Stelazine), thioridazine (Mellaril), fluphenazine (Prolixin), and clozapine (Clozaril). By the 1990s, newer medications like risperidone (Risperdal), olanzapine (Zyprexa), and quetiapine (Seroquel) came into use. These drugs often improved patients’ lives, though they came with side effects, sometimes really awful side effects.

Today’s Medicine Today – No Great Shakes

Today, the standard approach to treating schizophrenia starts with a detailed evaluation. Doctors gather information about symptoms, trauma history, substance use, and medical history. They assess the patient’s mental and cognitive state, as well as risks for suicide or aggression. If psychosis is confirmed, an antipsychotic medication is almost always prescribed.

Wake Up, Medical World – Speed Is Important

But here’s the problem: this process is often slow. Weeks, months, or even years can pass as doctors try one medication after another, with patients remaining in a psychotic state as one after another medication is tried. The mindset is often, “We are trying.”

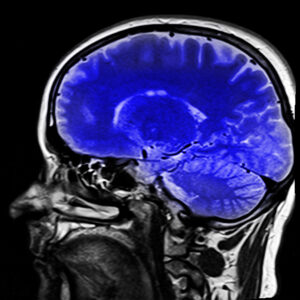

However, these past several years medical science has realized something alarming. Psychosis is toxic to the brain. It’s like brain poison. The longer someone stays psychotic, the harder it becomes for their brain to recover. This discovery has shifted the way we think about treating schizophrenia.

Oh, By the Way, Welcome

Welcome to the Neuroscience Research and Development Consultancy website. Have a question or a comment? Send it to us at: Comment@NeuroSciRandD.com

Part II. New Information & A New Treatment Plan for Schizophrenia

With Realizing that Psychosis is Toxic to the Brain, a Revolution in Schizophrenia Treatment Starts

Why Treatment Needs to Start Fast

Since psychosis damages the brain, it’s critical to treat it immediately. At the first signs of trouble, effective medication treatment must begin. Waiting for a confirmed diagnosis could cause irreparable harm to the person’s brain. It’s similar to the situation in medicine when an antibiotic for an infection is started before the exact bacteria is identified. Acting quickly prevents the illness from getting worse. It’s important to start even if details need to be worked out later.

Start Your Engines and Hit the Accelerator

This rapid-response approach works for people of all ages, from children to the elderly. Early treatment improves the chances of a full recovery from psychosis and reduces the likelihood of future psychotic episodes, hospitalizations, and life disruptions. It’s the difference between someone being able to date, finish school, and hold a job versus struggling with a major lifelong disability.

Polish That Crystal Ball and Predict the Future

Predictions are hard to make, especially about the future. (Some attribute this wisdom to the famous baseball player Yogi Berra, others say it came from the pen of renowned author Mark Twain.) But what if, instead of waiting for that first psychosis to appear, we could predict who is likely to experience psychosis even before it happens? That’s where biomarkers, medical clues like family history, brain health markers, and genetic background, come into play. These markers are helping doctors identify people at high risk for psychosis so that they can intervene early.

Healthy People with Healthy Brains Taking Antipsychotics

But that’s where this grand plan hits a dilemma. Not everyone at high risk ends up having psychosis. Studying these individuals may help us understand why some people develop the condition while others don’t, even with similar risk factors.

A Reader from Wyoming Asks: Does this actually work, or is it all just theory?

This reader, who said they lived in Wyoming, wrote to say that that whole mental illness schizophrenia area seems medically ill-defined. Maybe it’s all nonsense. So, it feels like speculation on nonsense to propose that an illness we’re not even sure exists in the first place can be eliminated by drugs.

We appreciate all feedback from each of our readers, and thank the reader for writing. That said, we clearly would take issue with this reader. We view psychosis as a well-established brain disorder, and further, a disorder that is toxic to the health of the brain. But our reader might have a valid point that is not immediately obvious.

Using the term “schizophrenia” has been criticized by learned and astute physicians and medical researchers. (See below the reference to the paper, “Eliminate schizophrenia”.) Even in medicine, even in psychiatry, the label “schizophrenia” is used to refer to many, many medical conditions. And the symptom of psychosis is seen in people who don’t have “schizophrenia”. They argue that the word is just a label and not a useful diagnostic term. It’s not a disease one can nail down with any certainty. These experts feel that medical science and practice should refer to the basket of problems that land under the schizophrenia label with a broad, ill-defined basket label, like “psychosis spectrum illnesses” until the science can tease out what is what with some better level of certainty.

Part III. The New Plan Hits Rough Water

At First It Seemed Like Such a Great Idea.

But, Treating People Who Are Well, Who Might Never Get Sick?

New discoveries often come with challenges. How’s this for a challenge. About half of the young people identified as high-risk for psychosis never develop it. That’s quite a hurdle to jump for this idea of treating the first episode of psychosis before it starts. Some high-risk-for-psychosis Individuals have been followed for over ten years to see if they ever become psychotic. Nope, they did not, or at least about half of them did not. But, many of that half who never become psychotic did fall ill with other psychiatric conditions, such as depression and anxiety.

Antipsychotics for Healthy People

You see the dilemma that this whole situation creates. The logical reasoning of this path is that we should give antipsychotic medications to people at high risk BEFORE they become psychotic. But, half of them will never become psychotic. Should we give these potentially harmful medicines for psychosis to healthy people who might never become sick? No, probably not. The drugs used to treat psychosis do have side effects. Some of them are really problematic side effects. Like weight gain, diabetes, and heart problems. Plus, just the act of telling a healthy person that they’re at high risk for some day becoming psychotic would upset about anybody. Such “news” could ruin a person’s whole outlook on life.

It’s One Thing If They’re Already Psychotic…

So, let’s back up for a moment. This is an easier decision if psychosis is already present. It’s clear that an existing and present psychosis, even the first hints of a real psychotic episode, need to be treated immediately. This immediacy is backed by strong medical evidence. But there’s little evidence for preventing a psychosis with antipsychotics just because an individual is identified as a high-risk. When there isn’t any hint of psychosis and they’ve never had a psychotic episode, why do anything? Though some experts advocate for pursuing less risky interventions in these identified-high-risk people, like psychotherapy or social support. It might be that these therapies are just as effective at preventing psychosis without the side effects.

Then There Is That Risk of Depression and Anxiety

Here’s another perspective. As we said above, among the group of high-risk individuals who never develop psychosis, over half have other psychiatric disorders, mostly depression and anxiety. Though antipsychotics were designed to treat psychosis, they can often work really well to treat anxiety or depression. This raises the possibility that early treatment might prevent other psychiatric disorders, not just psychosis.

Oh, The Ethics of It All

Coming at this dilemma from an ethical perspective provides new questions but really no new answers. Treating someone who isn’t psychotic but is at high risk is tricky. It might be defensible to treat someone without their consent when they are psychotic. Someone in the middle of a psychotic episode might not even know who they are, or where they are, or what’s happening around them. It’s hard to say whether a truly psychotic individual can even give authentic informed consent for accepting to take a medication. Or, refusing it. It’s like saving the life of someone unconscious after a car crash. One just saves the life absent any consent or refusal. We save their life. But on the other hand, unlike a psychotic person who might not be capable of informed consent or refusal, individuals who are not yet psychotic can decide for themselves. They are able to weigh the potential benefits against the risks and make their own informed choice.

Part IV. Well, Good Grief, Now What Do We Do?

We’re in a Quandary: And, Current Studies are Giving Mixed Results.

Is There a Middle Ground Approach?

So, what’s the best way forward? Imagine someone at high risk of psychosis due to their family history, their genetic makeup, and their adverse life experiences. Their doctors present them with a set of options. Maybe watchful waiting with regular mental status monitoring. Or perhaps starting a therapy (like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy). Would they like to involve family members in this decision. Finally, would they like to start a medicine for preventing psychosis.

Could The Safest Option Be Opting for the Medicine?

Some argue that if someone is at extremely high risk, starting medication might be the safest option. For example, a woman at high risk might take an antipsychotic and avoid a future psychotic episode altogether, allowing her to live a normal life. Assuming any side effects are mild, this could be a great option.

Tailor-Made, Bespoke, for Clothes That Fit

Bottom line, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution. One cannot grab a dress or shirt off the rack and have it always be just right. It’s a medical debate that balances the promise provided by early intervention and a better outcome against the risk of over-treatment. Ultimately, individuals must be fully informed and then empowered to make their own decision, maybe starting with less invasive approaches like therapy.

When Is The Medication Route Absolutely Necessary?

We are left with the one clear mandate. if someone is already experiencing psychosis, immediate and aggressive treatment with medications is essential. Antipsychotics, combined with education, therapy, and social support, are the best way to protect the brain from the toxic effects of psychosis. Without medication, the other interventions are unlikely to succeed.

The Ultimate Goal is Health

The goal remains the same: to reduce the impact of schizophrenia on someone’s life and help them to live fuller, healthier lives. While the road is still uncertain, the commitment to finding better solutions continues.

Helpful Links:

From the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill – Early Psychosis Intervention

From the U.S. National Library of Medicine – Early intervention in psychosis: concepts, evidence, and future directions

Jennifer L Zick, Brandon Staglin, and Sophia Vinogradov. “Eliminate schizophrenia” in the journal Schizophrenia Research in 2022.